One of the best things about writing historical fiction is learning about the characters who were real people and not just born out of my imagination (that’s fun too!). It’s not easy to research someone who wasn’t famous during her life and died nearly a hundred years before I was born. There was much speculation about Bessie’s past, but not much I could confirm.

I had learned Bessie grew up in Canton, New York and that her given name was Annie Moore. Her parents emigrated from Ireland to the United States via Canada, but it was unknown where Bessie was born. Thanks to Irish genealogy sites, I found a baptismal record for her.

Annie Moore, a.k.a. Diamond Bessie, was born in Togher, County Cork, Ireland, and baptized on July 3, 1850.

Right then I knew I had to go to Ireland.

I hired a genealogist who specializes in the history of County Cork and he pinned down the homestead where Bessie was born. Her father was a tenant farmer (as most of the Irish were then), but surprisingly—and luckily—the family wasn’t destitute during the Great Famine when blight destroyed much of the country’s potato crops. One can only guess as to why the family left Ireland, but a plausible reason is that becoming a landowner in the United States was more stable and profitable than leasing land in their homeland. When the English invaded Ireland in the early 1600s, they virtually wiped out property ownership for the Irish.

The genealogist, Dr. Paul MacCotter, took me on a tour of Togher. The Moore family cottage is gone, replaced with a two-story home, but a barn from the mid-1800s still stands on the property. Nearby is a dilapidated stone structure similar to what Bessie’s family would have lived in: a two-room thatched cottage. Across the street is the church where Bessie’s family would have gone to Mass.

It was a truly memorable trip and I’m sure some of what I saw and felt will make its way into the final manuscript.

Other Research

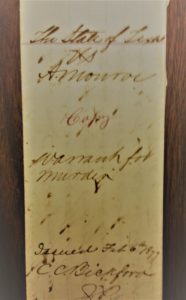

Jefferson’s newspapers covered Bessie’s murder, but unfortunately, very few articles survive from that time. Luckily, both newspapers in nearby Marshall, Texas covered the case extensively, and I spent countless hours scouring them. Some of the original court documents also survive, and I read those as well.

When I started my research, newspapers.com didn’t exist. Older newspapers are stored on microfilm or microfiche, and so that’s how I did most of my research in the beginning. As I learned of places Bessie and Abe had lived or visited, I used the interlibrary loan system to borrow newspaper reels from those cities. Of course, newspaper articles aren’t always accurate. They are a reporter’s observation or an account of information given to them by someone who may or may not be reliable. But when you do enough research, you start to see what’s erroneous and what’s accurate. Research is like a big jigsaw puzzle. There will always be a few missing pieces, but you can figure out what the puzzle looks like from what you find.

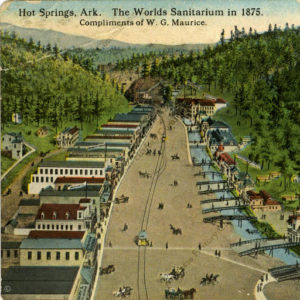

In addition to conducting research in Jefferson and Marshall and visiting Ireland, I also traveled to Chicago, where Bessie worked at a parlor house (what the high-class brothels were called); to Cincinnati, where Abe was from and where Bessie also worked at a parlor house; Hot Springs, Arkansas, where Bessie and Abe first met; New Orleans, where Bessie wintered; and Bessie’s hometown, Canton, New York, where I spent a day with the town historian.

In addition to conducting research in Jefferson and Marshall and visiting Ireland, I also traveled to Chicago, where Bessie worked at a parlor house (what the high-class brothels were called); to Cincinnati, where Abe was from and where Bessie also worked at a parlor house; Hot Springs, Arkansas, where Bessie and Abe first met; New Orleans, where Bessie wintered; and Bessie’s hometown, Canton, New York, where I spent a day with the town historian.

In each city, I drove around to see the places associated with the couple, but unfortunately, nearly everything was gone. I’ve found photos of many of the buildings, which is helpful of course, but it would be nice to walk through the Brooks House to see the room where Bessie and Abe stayed in Jefferson, or tour the opulent Burnet House in Cincinnati, where Abe lived. Those are just two examples of the dozens of buildings I looked for that no longer exist.

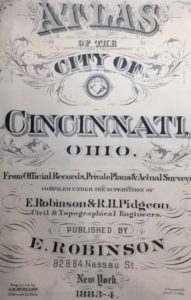

I visited the historical societies and museums in each city, and the public libraries. In Cincinnati, I found an atlas of the city from 1883 and spent hours at the library making 11″ x 14″ copies of each section, and then piecing them together when I got back home. The map was large enough to cover my dining room table!

I visited the historical societies and museums in each city, and the public libraries. In Cincinnati, I found an atlas of the city from 1883 and spent hours at the library making 11″ x 14″ copies of each section, and then piecing them together when I got back home. The map was large enough to cover my dining room table!

One of my favorite trips (besides Ireland) was to Edmonds, Washington, north of Seattle, to visit the daughter of a man who had seen Bessie on the streets of Jefferson as a young boy. Ed McDonald had been captivated by Bessie’s beauty. His daughter, Aree Risley, left Jefferson as a young woman to settle with her husband in Washington state. She shared many memories of her childhood in Jefferson. Aree was in her early nineties when we met; she died two months after my visit.

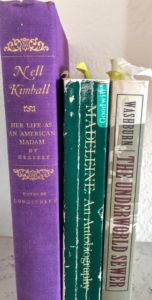

I also read–a lot–about life in the late nineteenth century. My most interesting finds were three autobiographies of late nineteenth/early twentieth century prostitutes. Talk about fascinating stories! These books contain a wealth of information about every aspect of a prostitute’s life, including what led women back then to become prostitutes.

I also read–a lot–about life in the late nineteenth century. My most interesting finds were three autobiographies of late nineteenth/early twentieth century prostitutes. Talk about fascinating stories! These books contain a wealth of information about every aspect of a prostitute’s life, including what led women back then to become prostitutes.

You can see a bibliography of my sources by clicking here.